These introductory bars became world famous through Stanley Kubrick’s film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” which premiered on April 2, 1968.

Kubrick’s space epic tells a mystical, mythological story of human evolution over a period of 4 million years. The main plot of the film, set in 2001, shows astronaut Bowman experiencing an odyssey in space, at the transcendent end of which Bowman is reborn as an astral “star child” immediately after his death.

The film, considered a masterpiece, offers room for various allegorical and philosophical interpretations. Even before the first manned moon landing and decades before the development of digital image animation, Kubrick delivered realistically perceived images of space through the innovative use of camera and optical effects techniques.

Newly composed film music was considered by Hollywood producers to be an extremely important factor in marketing and was considered to be an essential part of any advertising campaign. However, Kubrick decided, not necessarily by choice, to use an existing classic as the film’s theme song – the tone poem “Also sprach Zarathustra” by Richard Strauss. The whole musical work is quite complex and based on Nietzsche’s philosophical novel. The book, in turn, is structured like a classic epic, with many episodes in which the prophet-like Zarathustra tells parables or comments on various ideas and what is wrong in the world.

The name Zarathustra is well known to the general public thanks to Nietzsche’s novel, the first part of which was published in 1883. In this book “for all and none”, Nietzsche has his Zarathustra, whose name is “both dear and difficult to him”, proclaim the death of God and the (often misunderstood) doctrines of the superman and the “great noon”.

The high or great noon is mentioned for the first time at the end of the first part of Zarathustra, in which Zarathustra takes leave of his disciples to wander back into his solitude. The great noon designates there an event lying in the future, in which the human being stands on the middle of his way between animal and superhuman; just as the sun reaches the half of its course between morning and evening at noon. At this moment, man – also like the sun – stands at the highest point of his power of knowledge and radiation. Here he now understands the necessity of his own downfall, the leveling of his species as a requirement for the birth of the superman.

The great noon is thus closely connected with the concept of the superman and should remind the disciples at this point one last time of the preliminary core of Zarathustra’s teaching. Here the association of the cyclic course of the sun with an eternal repetition of the same – as it would fit to the doctrine of the eternal return – steps into the background. Rather, it emphasizes an association of the linear rise and fall of the sun with the rise and fall of humanity, which is thus better suited to illustrate the superman. Here, it is definitely worth comparing the plot in the film with Nietzesch’s philosophy.

It is still not possible to reconstruct exactly how Nietzsche came up with the idea to call his lonely proclaimer of truth “Zarathustra”. In a later work, the “Ecce homo” (1889), however, he lays a track: Zarathustra was the first in history to see “in the struggle of good and evil the real wheel in the gears of things. Since the Persian Zarathustra was more truthful and braver than any other thinker, he of all people was able to see this “fatal error” like no other.

In the following, however, it is no longer about Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, but about the eastern (and still living) religion, which claims Zarathustra as its “founder”, “prophet” or “reformer”.

In quantitative terms, the religion of Zarathustra, with perhaps 130,000 followers worldwide, is not worthy of further attention. At the same time, however, it is considered one of the oldest religions in the world, and accordingly it is treated in almost all handbooks on the history of religion.

Let’s take a quick look at the sources. In the Greek literature Zarathustra alias Zoroastres (Zoroaster) is supposed to have been mentioned for the first time in the 5th century before our calculation of time (B.C.). At the same time, however, we may assume that he was much older, because our informant, Xanthis the Lydian, knows to report that Zoroaster, the Persian, had lived 6000 years before the year 480, when the Persian Great King Xerxes crossed the Hellespont.

However, they do not give us reliable answers to our questions about Zarathustra’s time and place of life.

There are other “facts”, and these are even more difficult to judge. They consist in the fact that the name Zarathustra (actually “Zarathushtra”) occurs in ancient texts, which are still recited today by Zarathustrian priests and laymen in rituals and prayers. These texts are written in an ancient Iranian language called “Avestic”. The collection of these ritual texts is called “Avesta”. A special script was probably developed for writing down these texts between the 5th and 7th centuries AD, after they had been passed down orally for the longest time.

In the arrangement in which the texts have come to us, the sacred forms frame two somewhat longer texts: a litany of worship. which is in the center, as well as five songs (Gatha), which are particularly important for our question, because in them a person named Zarathustra appears several times and in a central place.

Here we would like to end this philosophical lunch journey again and come to the following, relatively courageous conclusion:

If we compare the Avestic word “Gatha” with the related Indian “Gita” from Sanskrit, we all agree that they are almost identical in their fundamental form. In both languages, it translates as “Divine Chants (or Hymns).” Gatha, Gita, God, Gothic, goodness, good, seem purely acoustically enormously related – however etymologically or better said scientifically no relationship is assumed.

In this regard, we still wish you a good appetite and a good gut feeling.

(Sources & inspiration: Michael Stausberg – C.H.BECK, Wikipedia)

Related Posts

March 9, 2023

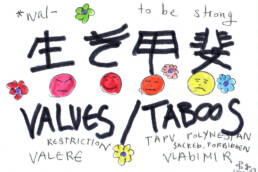

Values or taboos? Ikigai or Shinigai?

At the turn of the 19th century, Kant asked, “Why is work the best way to…

September 30, 2022

Content Creator

Joseph Beuys, probably the best known and most influential German artist of the…

September 9, 2022

Postmodernism

Actually, there is nothing wrong with saying that we live in the modern age.…